I Bet You Thought Vespa Only Made Scooters: The Vespa 400 Car

Posted on Aug 18, 2014 in Editorials | 1 comment

Our friend Mr. Baruth is on a bit of a motorcycle kick lately and, while he’s not quite ready to cruise the interstate highways on a Honda Gold Wing, he recently described the Wing as “one of those brilliant products that both defines a market segment and then comes to utterly dominate it.”

The same could be said for another two-wheeler, though one that couldn’t be more different from the Gold Wing. I’m talking about the Vespa scooter: Introduced in war torn Europe in 1946 and used as basic transportation by Italians rebuilding their country, the Vespa scooter became a bit of a fashion statement by the 1960s (and an essential accessory for the Mod craze in England). It’s been adopted by the developing world as basic transport in the decades since then, and is once again becoming a fashion statement in the 21st century. Virtually every motor scooter made in the last 70 years has followed the Vespa’s template.

This post, however, isn’t about a Vespa scooter. It’s about a Vespa car.

First, though, some scooter history is necessary before we move on to four wheelers.

While the Vespa brand is internationally famous today, it’s the product of an old Italian company started by the Piaggio family that fitted luxury ships in the 19th century. By the turn of the 20th century, Piaggio had started making rail cars, delivery vans, luxury coaches, streetcars, truck bodies and engines. During the first World War, in which Italy joined with the UK, France and the United States to battle Germany, the company expanded into making airplanes and seaplanes for the military.

After WWI, Piaggio acquired a small factory in Pontedera, which it then devoted to making aircraft and parts — including propellers and engines of its own design. During World War II, Italy was this time fighting on the side of Germany, and that plant produced the highly regarded P108 bomber with its four 1,500 horsepower Piaggio engines.

That factory, however, ended up being destroyed by both sides in the conflict. After the Allied invasion of Italy, the retreating Germans moved some of the machinery to Germany and mined the pillars that were holding the building up, damaging it beyond use. In August 31, 1943, Allied bombers completely leveled what remained. The Allied forces soon occupied Pontedera and some forces were bivouacked in what few undamaged buildings were on Piaggio’s property.

The Vespa’s story somewhat parallels that of the post-war Volkswagen Beetle, though it was a member of the Piaggio family getting production going instead of a British officer. After the end of hostilities, Enrico Piaggio, son of the company founder Ricardo Piaggio, was then in charge of the family business. He approached the Allied officers in charge of the occupation and requested permission to rebuild the plant using machinery located at Piaggio facilities in northern Italy and what could be recovered from the machinery in Germany stolen earlier by the Nazis. Permission was granted.

Now that the Piaggios had a factory and machinery, they needed a product to build with them. During the war, the company had made a small motorcycle intended to be dropped and used by paratroopers. Rebuilding after the war, Italians needed basic transportation. Based on that military two-wheeler, a prototype scooter was designed, but Enrico Piaggio didn’t like the looks of it and asked aeronautical designer Corradino D’Ascanio to redesign it.

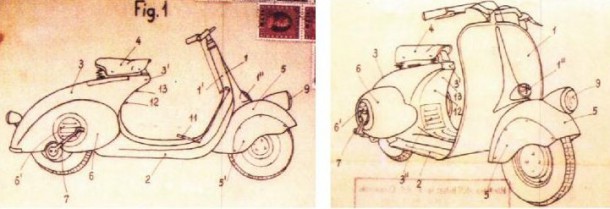

Corradino D’Ascanio’s patent drawings for the Vespa scooter.

Though he’ll be known for the ages as a scooter designer, D’Ascanio was a notable aircraft designer and actually designed the first production helicopter for Agusta. D’Ascanio wasn’t a fan of conventional motorcycles. In fact, he’d never designed a motorcycle or anything like it before.

Chain drives meant oil and grease got spewed, tires were hard to change and D’Ascanio found the riding position uncomfortable. Applying principles of aircraft design, he came up with a monocoque body. He eliminated the chain by integrating the engine and transmission into a compact, rear-mounted unit. To make it easier to change the front tire, he designed a single leading arm suspension carriage as one would find on an airplane instead of a fork. He gave it an upright riding position (but small wheels to keep the center of gravity low) and a front fairing integrated into the body that somewhat protected riders from the elements and flowed into running boards for the rider’s feet. It’s unquestionably a brilliant piece of design.

Piaggio MP6 “Vespa” Prototype

When Enrico Piaggio saw the drawings and the prototype’s bulbous, tapered rear end and narrow center section he said, “It looks like a wasp!” — vespa, in Italian — and that’s how the brand was named.

It was rushed to production and, by the end of 1946, Piag sold about 2,500 copies of the first Vespa powered by a 98cc engine. The following year, sales quadrupled, Vespa introduced a bigger 125cc model, and then sales doubled again in 1948, reaching almost 20,000 scooters.

By 1952, they sold over 170,000 units and had started licensing companies outside Italy to build the Vespa.

By the late 1950s, the Vespa was being made in 13 countries and being sold in 114. It spawned imitators from companies like Lambretta and even the USSR — then in “anything the West can do, the comrades can do better” propaganda mode — started selling the Viatka 150cc, a close copy of the Vespa.

Mike Hanlon at Gizmag sums up the Vespa scooter’s appeal:

Riding a Vespa was synonymous with freedom, with agile exploitation of space and with easier social relationships. The new scooter had become the symbol of a lifestyle that left its mark on its age: in the cinema, in literature and in advertising, the Vespa appeared endlessly among the most significant symbols of a changing society.

Rebuilding countries need commercial vehicles. As the VW Type II Transporter followed the Beetle, the three-wheeler Ape (Italian for bee) commercial truck/van followed the Vespa (though chronologically, the Ape predated the Type II by a few years).

Note the warning to remember to mix oil with the gasoline to lubricate the two-stroke engine.

By the mid 1950s, a million Vespas had been sold, but two wheels and exposed riding is not appealing for a lot of people. Europe was recovering beyond scooter stage and there was a flourishing of microcars that suited both the increased expectations and limited resources of societies rebuilding after a war. Piaggio decided to expand the Vespa brand to four wheels.

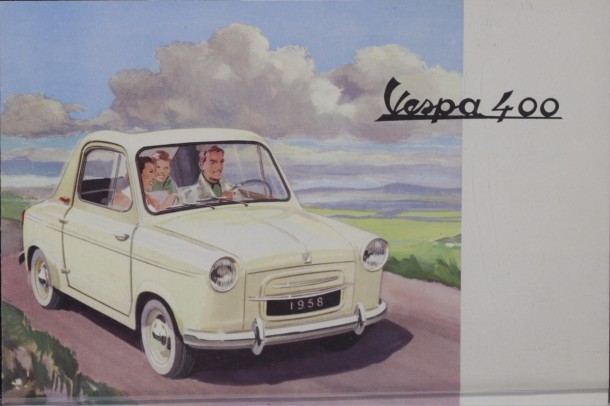

As early as 1952, Vespa’s facility in Genoa had started building a small convertible, but the company didn’t seriously pursue mass production of automobiles until the mid 1950s. A prototype was developed in 1956 and first shown to the public as the Vespa 400 in September 1957.

Though designed by Corradino D’Ascanio and engineered completely in Italy by Vespa, assembly was jobbed out to Ateliers de Constructions de Motos et Accessoires (ACMA), which was already making Vespa scooters under license at their factory in Fourchambault, south of Paris. It’s said by some that the Agnelli family, who controled Fiat, exerted some pressure to have assembly of the Vespa 400 moved out of Italy so as not to compete with the then-new Fiat 500.

Perhaps Fiat’s concern was at least partially justified because the Vespa 400 isn’t really like most microcars, which weren’t very sophisticated. Instead, the Vespa was a fully engineered automobile, only miniaturized; the minimum needed to carry two adults and maybe a kid or two, much like an early version of the original Tata Nano.

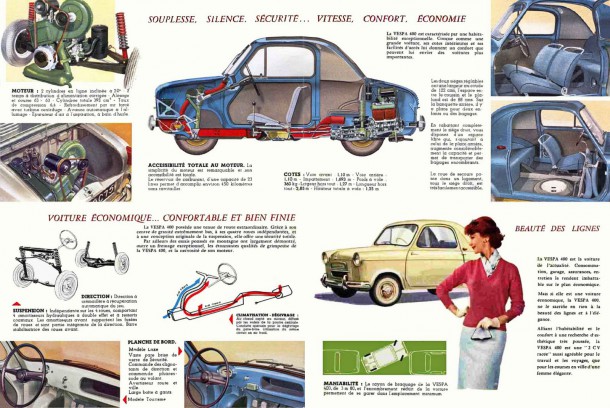

Again, using aircraft techniques, D’Ascanio gave the Vespa 400 a light and strong unit-body monocoque. Most microcars used scooter engines like the single-cylinder Sachs 175cc two-stroke. The Vespa 400 had, as you might guess from the name, a 400cc engine (394 to be precise) — an aluminum, air-cooled (with integral cooling fan) two-stroke vertical twin purpose designed for the car. With twin coil ignition, it put out 14 horsepower through a three-speed (or optional four-speed) gearbox. The drivetrain was mounted in the rear. The electrical system was 12 volts. It had rack and pinion steering (with kingpins) and all four corners were suspended independently with coil springs with a front anti-roll bar. The independent rear suspension used a lower control arm and a coilover spring/shock strut; not terribly different than the “Chapman strut” layout used on the Lotus Elan and Toyota 2000GT. Brakes were hydraulic, with 6.75-inch drums inside 10-inch wheels. Those 4.40X10 inch wheels were made specifically for the 400, not shared with the scooter or Ape. You may laugh at 10-inch wheels, but that’s what the original Mini was rolling on just a few years later. At 9-feet-5-inches long, the Vespa 400 was more than a half foot shorter than the Mini, with a 67-inch wheelbase.

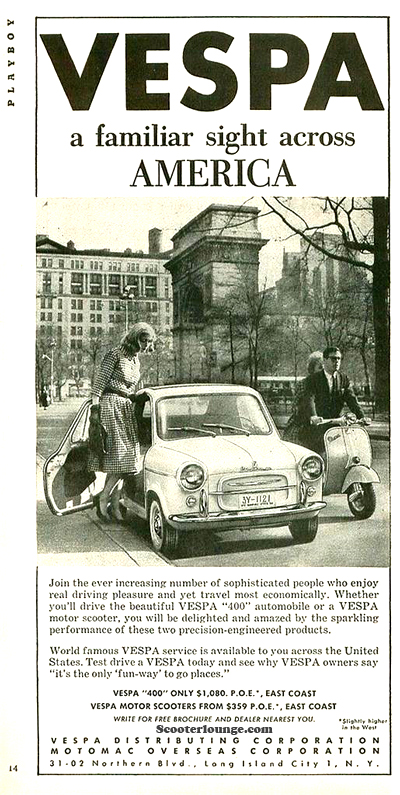

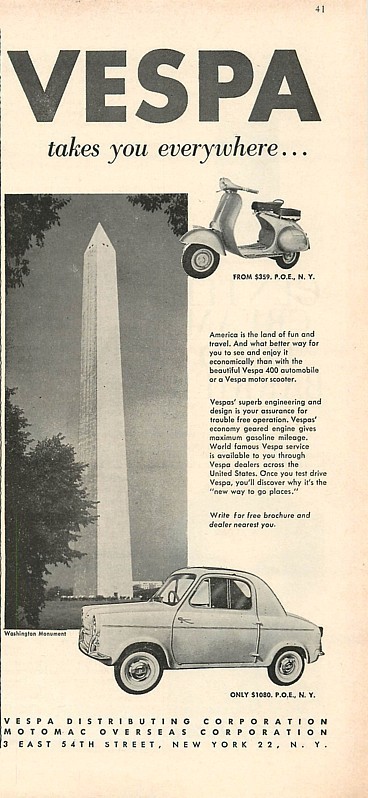

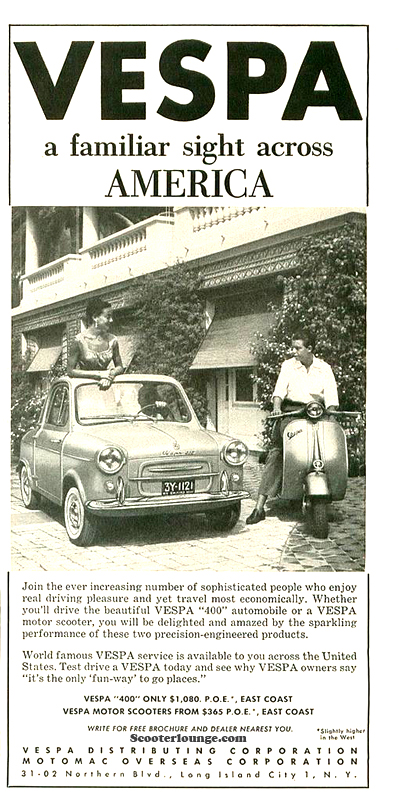

Ford and Chevrolet each sold about a million of their sedans in 1955. Vespa sold about 1,700 Vespa 400s in four years in America, and about 28,000 worldwide. It was not that familiar of a sight.

You can’t find a 0-60 mph time for the Vespa 400 because its claimed top speed was just 50 — which could be reached in just 25 seconds. According to Wikipedia, Motor magazine in the UK tested a 400 in 1959. They measured a top speed of 51.8 mph, acceleration of 0-40 mph in 23.0 seconds, and a fuel consumption of 55.3 miles per imperial gallon (5.11 L/100 km; 46.0 mpg-US).

There isn’t much storage space. There’s a slide out drawer in front, but that space is shared by the battery. The spare tire is stored under the passenger seat. As it’s a two-seater, the 400 has a parcel shelf in the back that could accommodate a couple of small children with an optional cushion. The front seats were cloth panels elastically suspended from tubular metal frames. Between them was the handbrake, ignition switch and choke control with the gear change a bit forward of them. The doors were rear hinged and had only the barest minimum of a plastic liner on the inside. The instrument panel includes a speedo, indicator lights for the high beams and generator charging status, and turn signal indicators. There was no fuel gauge, just a warning light for low fuel. A heater, defroster and windshield wipers were standard. Perhaps as a nod to the Vespa scooter’s al fresco riding, all Vespa 400s had fabric cabriolet roofs that could be rolled back on steel side rails, leaving the car open from the top of the windshield to the deck lid in back.

This is possibly the first use of black models in car advertising in America.

While the Vespa 400 may have been spartan, at least one vendor offered a full range of accessories, both functional and dress-up.

Styling? Not bad; a bit reminiscent of Renaults of the era. The rolltop roof makes me think of another very small car — the Crosley.

Introduced to the press in Monaco and then to the public at the Paris auto salon in 1957, the Vespa 400 was initially a success, selling 12,000 units in its first year of sale in 1958. Exports were started and an American distributor, Motomac Overseas Corp., started advertising in publications like Mechanix Illustrated and Playboy. As a historical note, Motomac’s ad agency hired black models for some of their print advertisements. That may have been a first in America.

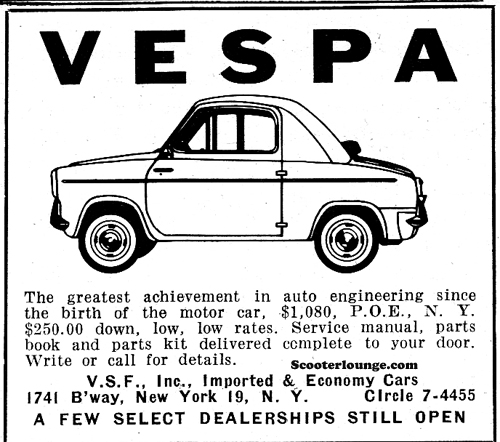

Their ads featured both the Vespa car and the “precision engineered” Vespa scooter. It was a time when many European car brands, seeing Volkswagen and the Rambler’s success, started importing their small cars here. Vespa was a known brand because of those scooters. V.S.F. Inc. Imported & Economy cars also apparently distributed Vespa cars as they advertised that a “few select dealerships” were available to sell what they billed as, “The greatest achievement in auto engineering since the birth of the motor car.”

I don’t know if he published a review or just got paid for the endorsement, but Vespa ads also quoted famed car reviewer Tom McCahill as saying, “Here is real fun… this car has a fantastic ride,” and commenting that it steered with the alertness of a Grand Prix car. Come to think of it, with the engine over the back wheels, the sophisticated rear suspension and rack and pinion steering, it probably did handle better than most of the cars McCahill was paid to tout reviewed.

Consumers and more impartial reviewers than McCahill complained of an awkward gear shifter, noise (there was no soundproofing to speak of), high fuel consumption and having to mix oil with the fuel to lubricate the two-stroke engine. Later models would feature a different carburetor and eventually automatic oil injection. Apparently, in time, there were two models available in Europe — Touring and Lusso. Lusso is Italian for luxury, but I’m not sure how luxurious it was.

Sophisticated as it might have been for a microcar, the Vespa 400 was in crowded territory by the time it hit the market. Vehicles like the aforementioned Fiat 500 and, by 1959, the original Mini were a little bit bigger and more substantial than the Vespa 400. The Mini and the VW Beetle could carry four adults and go twice as fast. At $1,995 vs $1,080 (U.S. POE), the Volkswagen was also twice as expensive as the Vespa car, but consumers thought it was more than twice the automobile. Even the Citroen 2CV, which had less power, was a larger car than the Vespa. Sales of the 400 dropped to about 8,700 in 1959 despite a price reduction. By 1961, the last of approximately 28,000 Vespa 400s rolled off the assembly line in Fourchambault. Piaggio has never again tried to market a Vespa car, though the parent brand sells the Piaggio M500 city car, a rebadged Casalini with a 505cc two-stroke engine, and has shown the Piaggio MT3 300 concept in India, a four wheeler based on Ape trike mechanicals.

Today, Vespa 400s are not very common, so you’d be excused if this is the first time you found out that Vespa made cars in addition to scooters. Just 1,700 were imported to the U.S.A. back when they were new, and unit-body cars of that era tend to rust to nothingness. They’re also a challenge to restore because parts are hard to find. Still, I’ve seen at least three Vespa 400s at Detroit-area car shows. Hemmings says that if you just gotta have one, you can find something restorable for about $5,000. Already restored examples are fetching as much as $15,000. Since you can find restored Vespa scooters from that era for about $4,000, it looks like doubling the wheels on your Vespa will cost you more than double the money.

I find your article very interesting and mostly true. However there are a few facts I would take to be incorrect. I am Larry Ray Newberry and I own Microcarlot in Knoxville Tn. We are the world wide parts supplier for the Vespa 400 car. We also do complete restorations of the cars. We built the Vespa 400 Jolly you mentioned. Not sure how you obtained your price figures, but are not in line with any that we have seen. We have sold several of the cars through private sales and the large auctions. we have never sold a restored Vespa 400 car for less than $25,000.00 I would think any research for the Vespa 400 car would have turned up our web site.